Min Hsin Chu Covers to Foreign Destinations By Sam Chiu If you were to ask an ordinary Chinese living at the turn of the century how they would send a letter to their friends or relatives who had the good fortune to be of in the United States ‘digging gold’1 , this would probably be their answer. Because many people were illiterate, they would go to the local letter writer and dictate a letter. They would then pay the letter writer a fee for writing the letter, the stationery and, of course, the postage. The letter writer would then take it to the a private letter company, perhaps a Min Hsin Chu or letter ‘Hongs’. Some of these letter writers actually worked for a private letter company. The letter would become part of the ‘clubbed mail’ and would be carried by the Min Hsin Chu's runners who travelled from city to city on land or by sea. Most of these letters would end up at the Min Hsin Chu's corresponding office in Hong Kong, given to the post office and forwarded to their destinations. Those who were literate would also bring their letters to the Min Hsin Chu who would transport them in the same way. Importance In China, Letter Hongs or Min Hsin Chus existed for hundreds’ of years. It was the only way an ordinary citizen would be able to send a letter until the formation of the National Post Office on Chinese New Year Day, February 2nd 1897. However, even after the formation of the national post office, the availability of postal services was restricted to the areas in and around the major population centres. It was not until the explosive growth of the number and locations of the post office and sub-offices around 1905-10, that postal services were more commonly available to the average person. There is a general lack of information or reference literature on this area which spans many years. This is due to a general lack of available material, documentation (hence knowledge) and philatelic researchers who can read Chinese. I will therefore venture to bring to your attention some of this history, the postal history of mail sent abroad by Min Hsin Chus from the 1890’s to early 1900’s. It is, of course, debatable how much philatelic importance one should attach to these letters delivered by ‘private’ letter hongs that were open to the public. I will make the following points: For those who are considering exhibiting in this area, the FIP definition for postal history is as follows: "Postal History exhibits contain material carried by, and related to, official, local, or private mails." I rest my case.

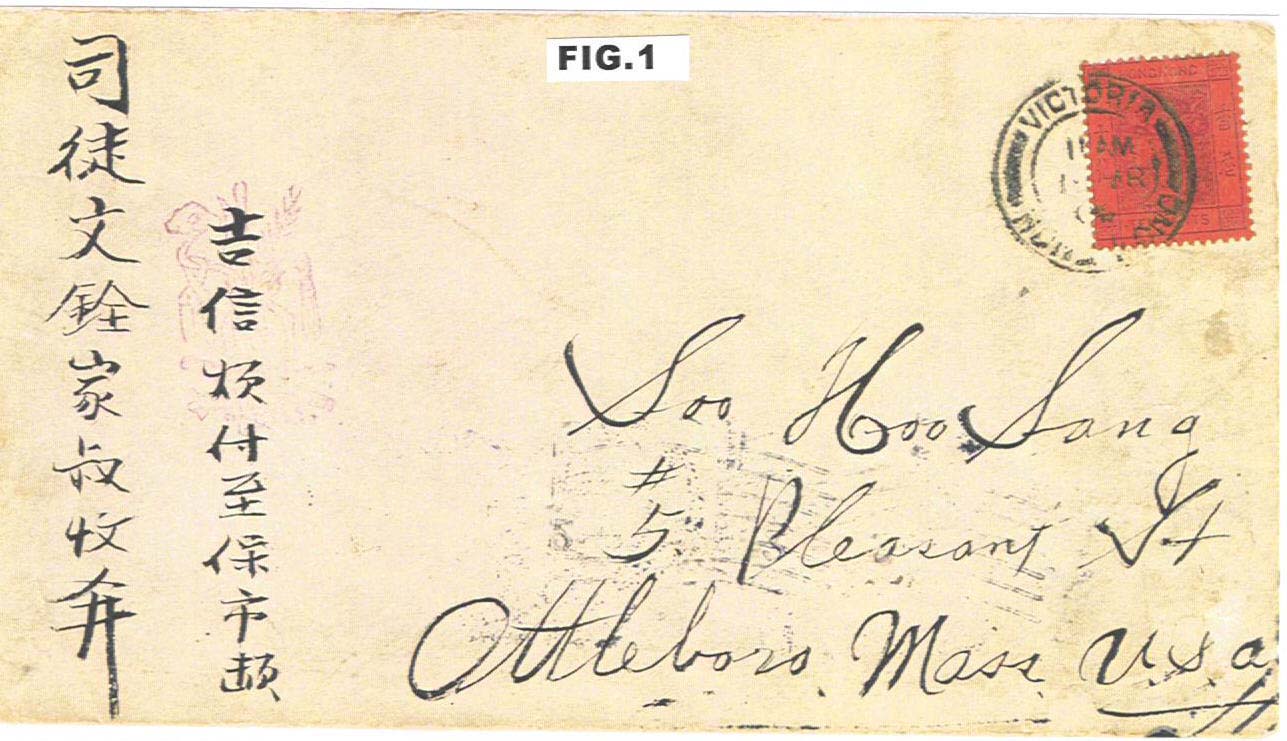

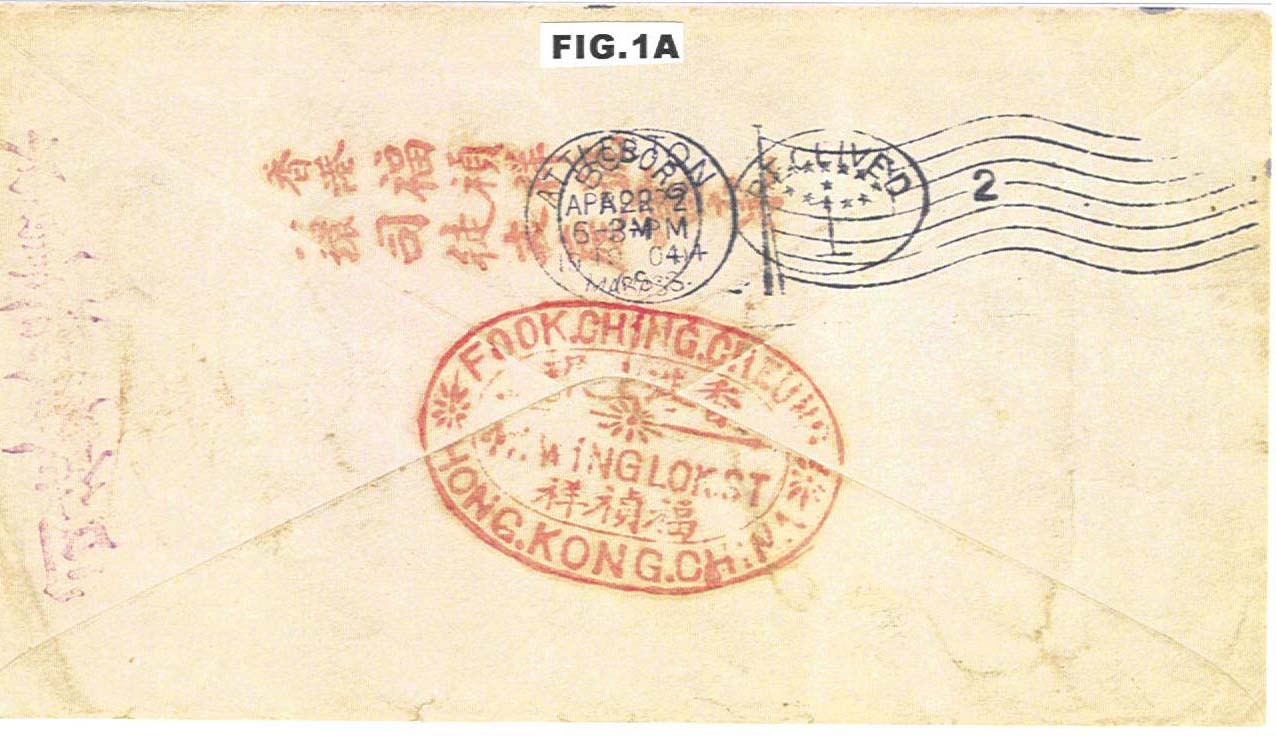

An ordinary Hong Kong to US cover Figure 1 shows an ordinary or vanilla HK to US 1904 cover. The back of the cover may indicate otherwise (fig. 1 A). On the right were 6 characters that can be translated as the writer's stationery/envelope/letter. Some would say that this was merely the letter writer's personal marking and of no significance. Then we see another marking with 2 rows of characters stating that it was the same writer's stationery/letter/envelope. But this time this marking had a commercial slant as it stated the company/firm's name and the location of Hong Kong Sheung wan. This may either be the company's marking or to advertise the fact this store sold this envelope or this can be the Min Hsin Chu's marking or the Min Hsin Chu's HK corresponding office. The double line oval was the commercial marking of the same company as the marking in the 2 rows of writing. The cover was addressed to Attleboro, Mass., but the Chinese address said Boston. Let us come back to this cover later. A common feature is that most, if not all, of these covers are franked with a single copy of the HK Queen Victoria 10 cents purple on red paper adhesive, cancelled in HK and were addressed to US destinations, except where it is noted otherwise. "This Letter Received From Min Hsin Chu" and other Directional Markings I bought this 1895 cover sent to Portland, Oregon, from a dealer who had found that this HK "Too-Late" marking on the front was not listed in Proud (fig. 2). The marking on the back (fig. 2A), just like the previous cover, had a HK commercial stationery/letter/envelope marking and the same firm's oval marking of ‘Vong Vuen Tong’. Furthermore, it had an additional two different markings: one of a commercial company ‘Cheung Vu Tong’ and a personal one ‘Cheung Mu Ming’. However, the most important marking was the 7 characters on the bottom, ‘This Letter Received From Min Hsin Chu’. This proved that cover originated from a Min Hsin Chu in the mainland and was forwarded to the corresponding letter office "Vong Vuen Tong" when it was taken off the ship at Sheungwan. This marking is of pivotal importance as it established in no uncertain terms the link between the Min Hsin Chu to the HK post office.

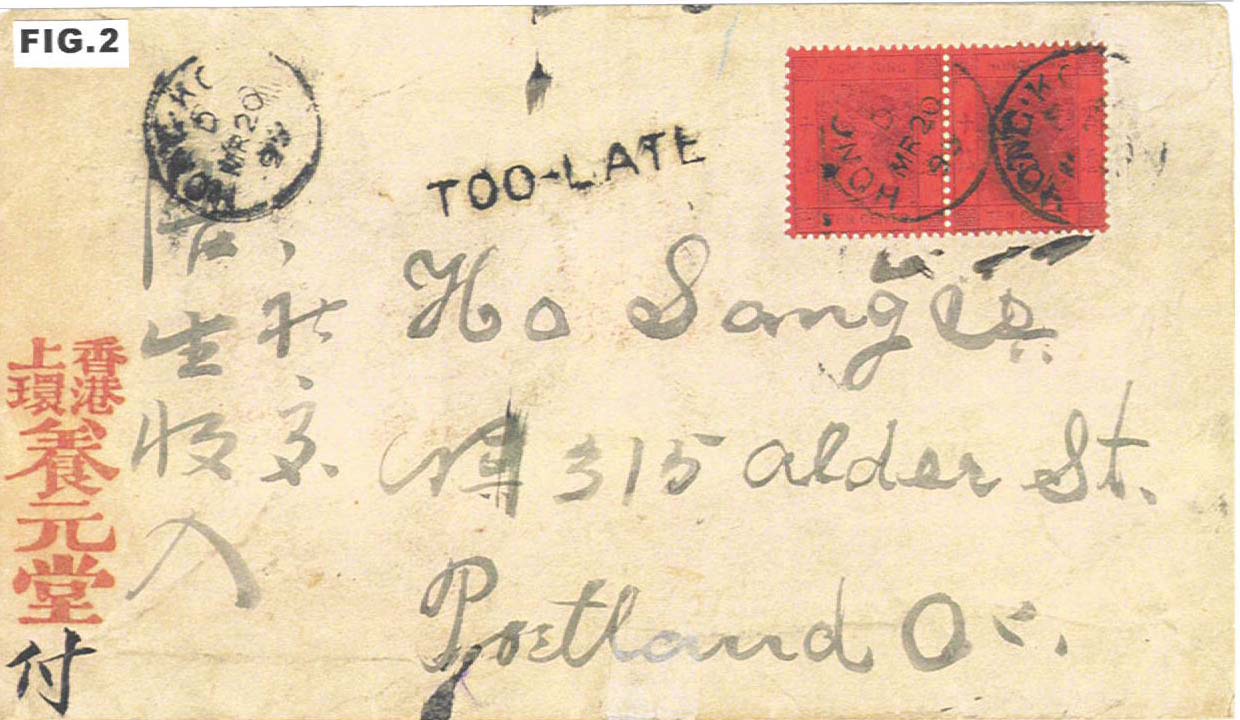

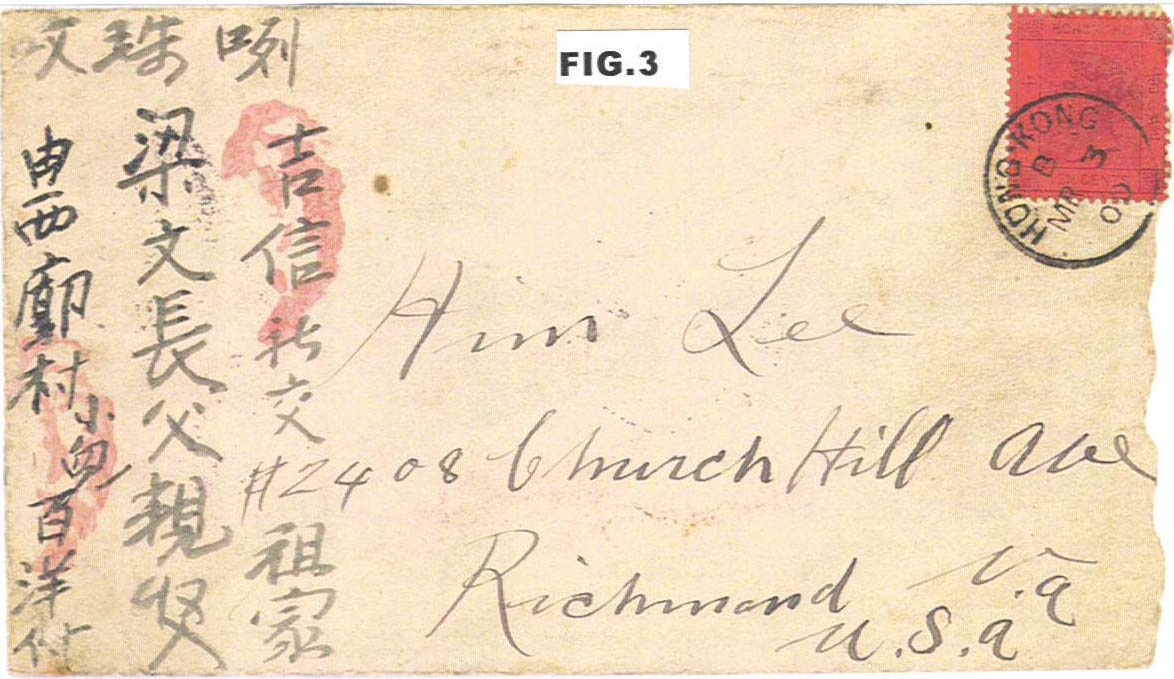

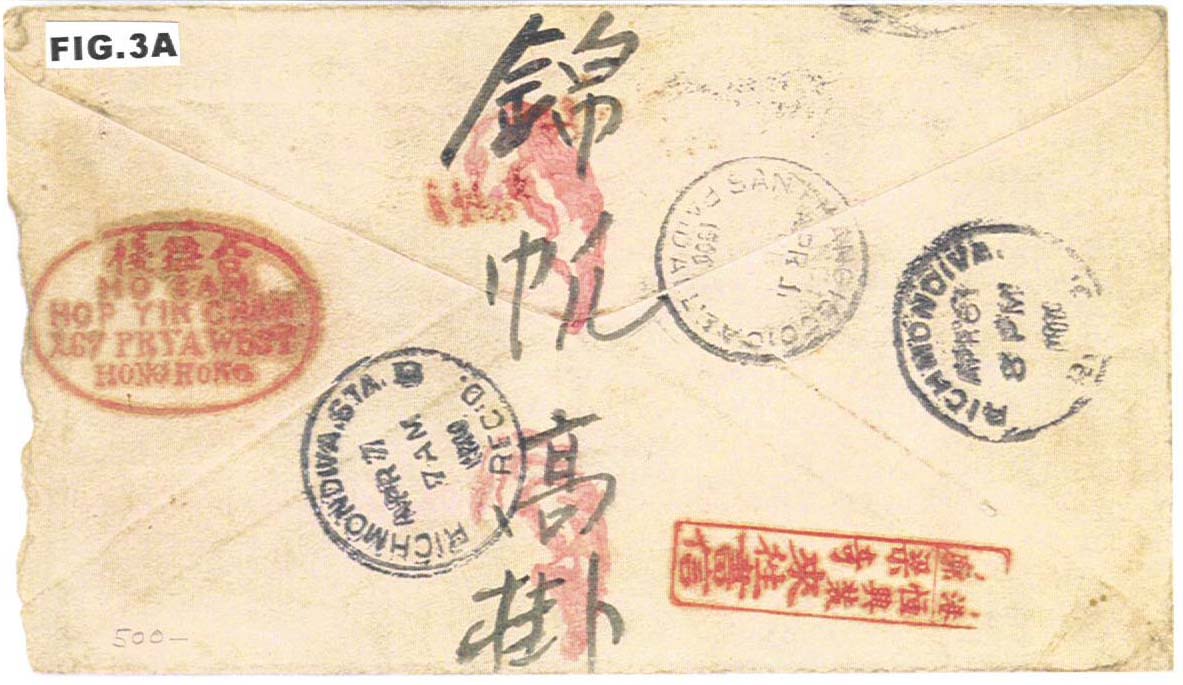

This cover has an additional feature in that the China ferry arrived too late to have it delivered to the Hong Kong Post Office, hence the ‘Too-Late’ marking. This cover has two copies of the QV 10-cents stamp with one paying the late fee. Trade from China, at the time, were all concentrated in the Sheungwan and West Point areas, with most of the ferries from China docking on the waterfront at Sheungwan. The only regrettable fact was that the originating city or village was not included in the Min Hsin Chu, Cheung Vu Tong's marking. Figure 3 shows another example. This was a 1900 cover from Sei Kok Village (somewhere in the Pearl River Delta) via HK to Richmond, British Columbia, Canada. On the back (fig.3A) is a boxed inscription and other markings.

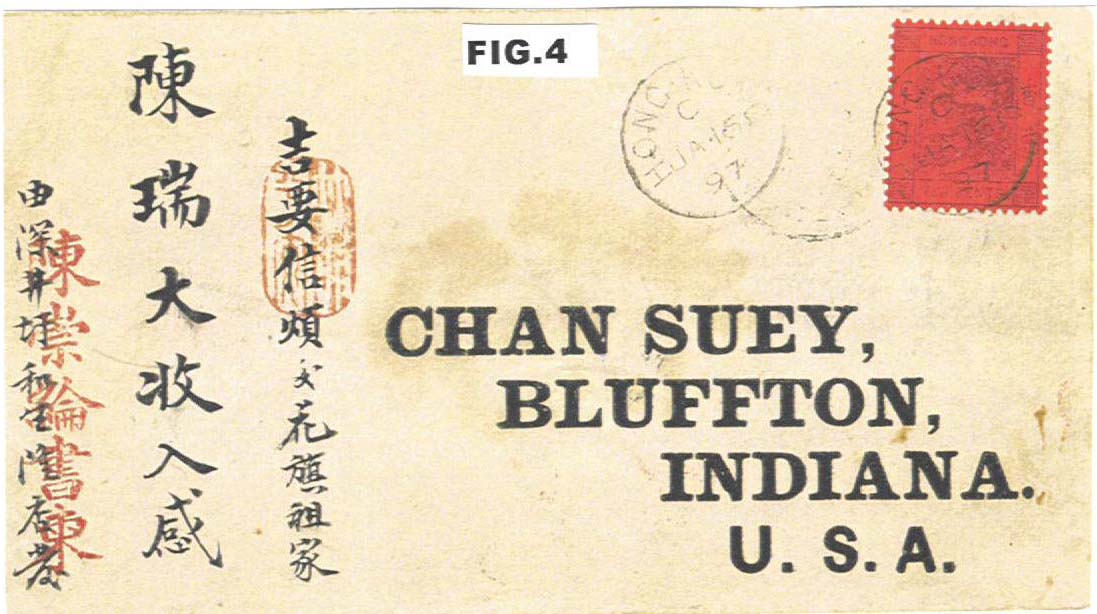

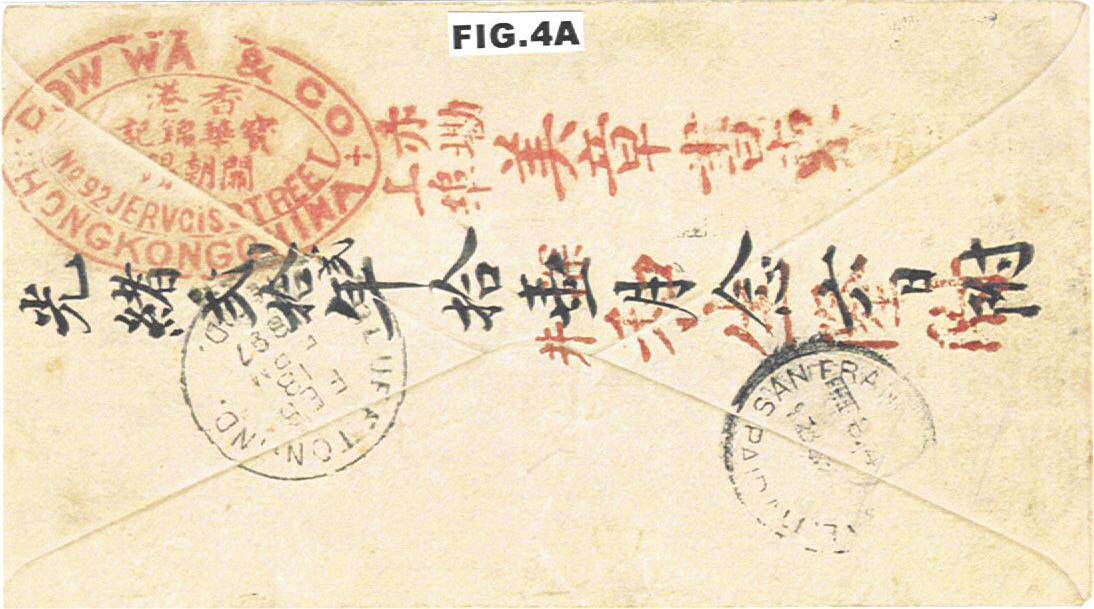

Other examples of Min Hsin Chu covers sent via the Hong Kong Post Office to foreign destinations Let me be the first to say that these covers are not rare. Most covers of this period that were addressed to foreign destinations would be handled in the same sort of way, which meant these would receive similar markings. The ones that originated strictly from HK are not in the scope of this article. However, the covers in fig. 2 and 3 are rare and important because of the presence of the directional markings. There are of varying degree of importance (or if you prefer, desirability). To illustrate this point, look at the back of this 1897 cover to Bluffton, Indiana (fig. 4 & 4A). This cover has a HK oval ‘Pow Wa & Go.’ marking, a ‘from Sum Gheng Woo Sung Loon’ marking and a Ghek Hom ‘Mei Gheung’ stationery/letter/envelope marking. Aside from the fact this originated from a fairly distant and sparsely populated city of Ghek Hom in Kwangsi, the fact that this letter was relayed between three Min Hsin Chus must make this cover rare.

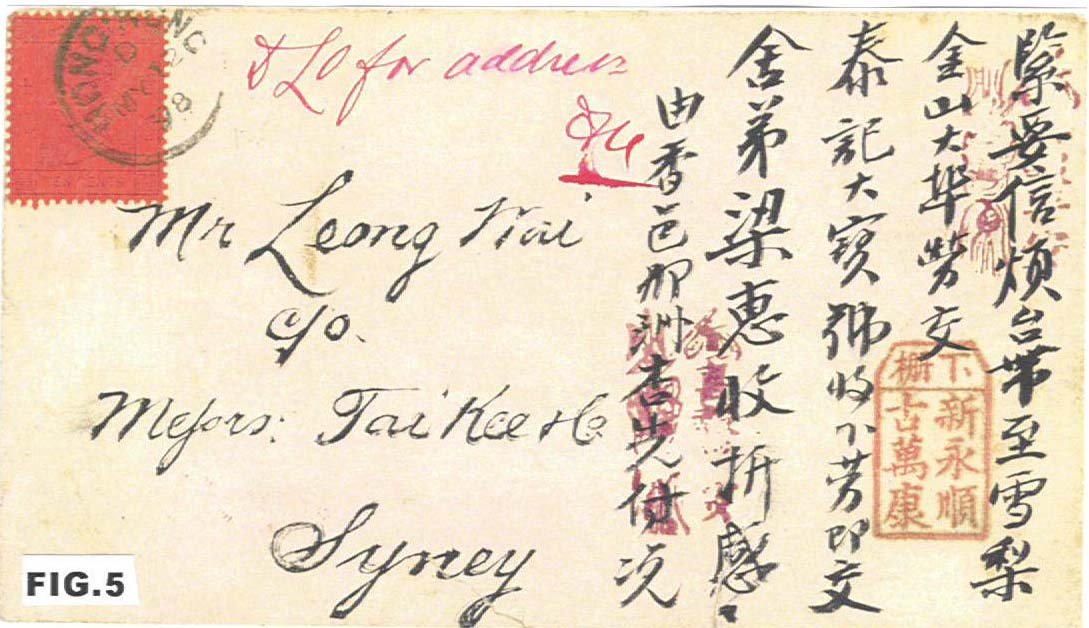

Another subtle but important feature was the date of January 16th, 1897 cancelling the stamps in HK. In Pratt's book (cited earlier), it was reported that the Director General of Post signed an agreement with the shipping companies in the middle of January 1897. From that time on, Min Hsin Chu mail, like this cover, was banned from shipment by most of the shipping companies. This one made it before the ban. Another cover that was shipped to HK despite the ban was a 1898 cover to Sydney, Australia (fig. 5). This had a tombstone marking indicating the Min Hsin Chu at Ha Chap ‘Shing Wing Shun, Koo Man Hong’. It was sent at Huen Yap's Ying Chow.

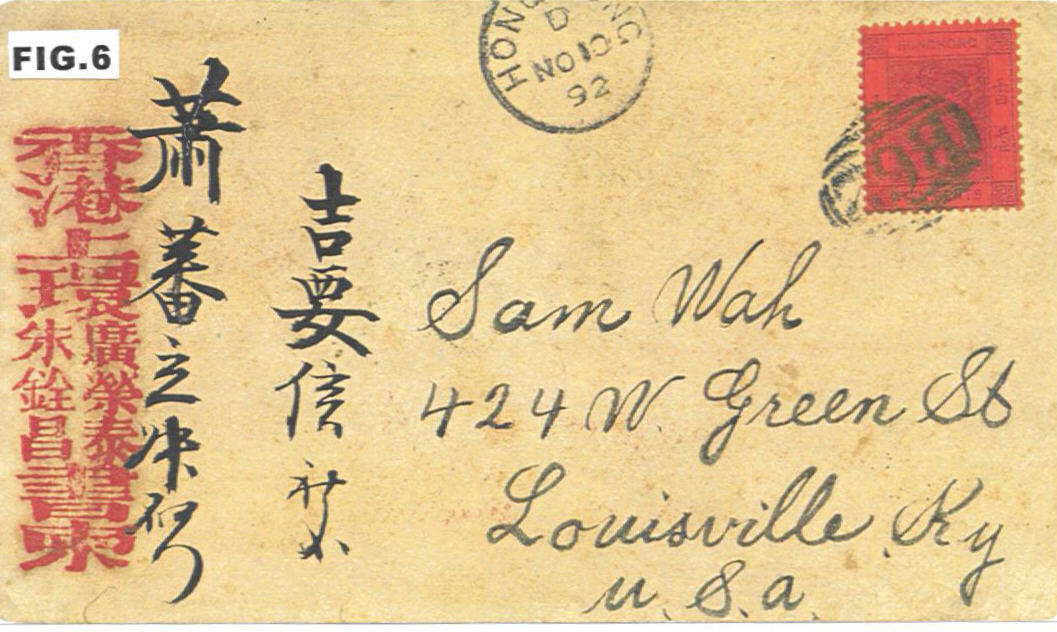

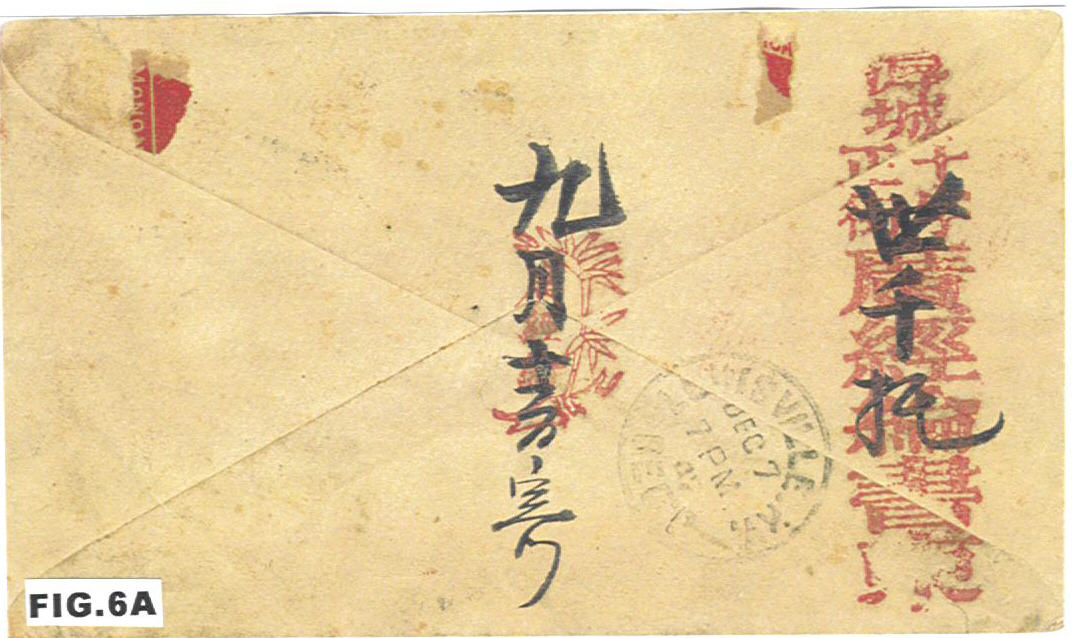

The philatelic researcher is hampered by a lack of contemporary maps pin-pointing the location of these small villages or towns. An additional feature on this cover is the words ‘D.L.O for address’ (DLO is the Dead Letter Office). There is also two strikes of a marking that featured leaves and four characters "happy to report tranquillity". These markings were used as auspicious signs. The writer used ‘Gold Hill’ generically to refer to Sydney, in this case.2 One of the earlier Min Hsin Chu covers to HKPO I have seen is a 1892 cover to Louisville, Kentucky (fig. 6). On the back (fig. 6A) is the marking Tui (?) Shing (City) Sap Che Jing Kai (Street) ‘Kwong King Lun’ stationery/letter/envelope. Not only did this marking include the city, it also stated the street where the Min Hsin Chu was located. It also had an good luck sign of a plant with the name of the company stamped as a seal on the back flap. The Hong Kong Sheungwan corresponding office had it’s marking ‘Kwong Wing Tai’ on the front.

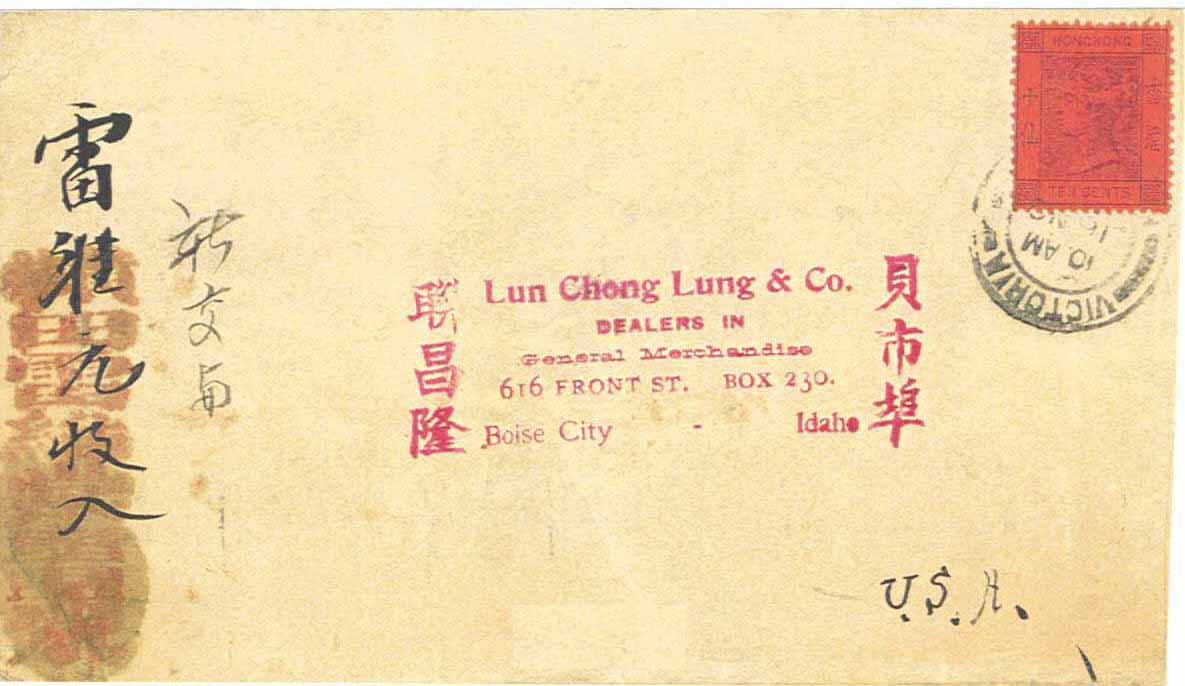

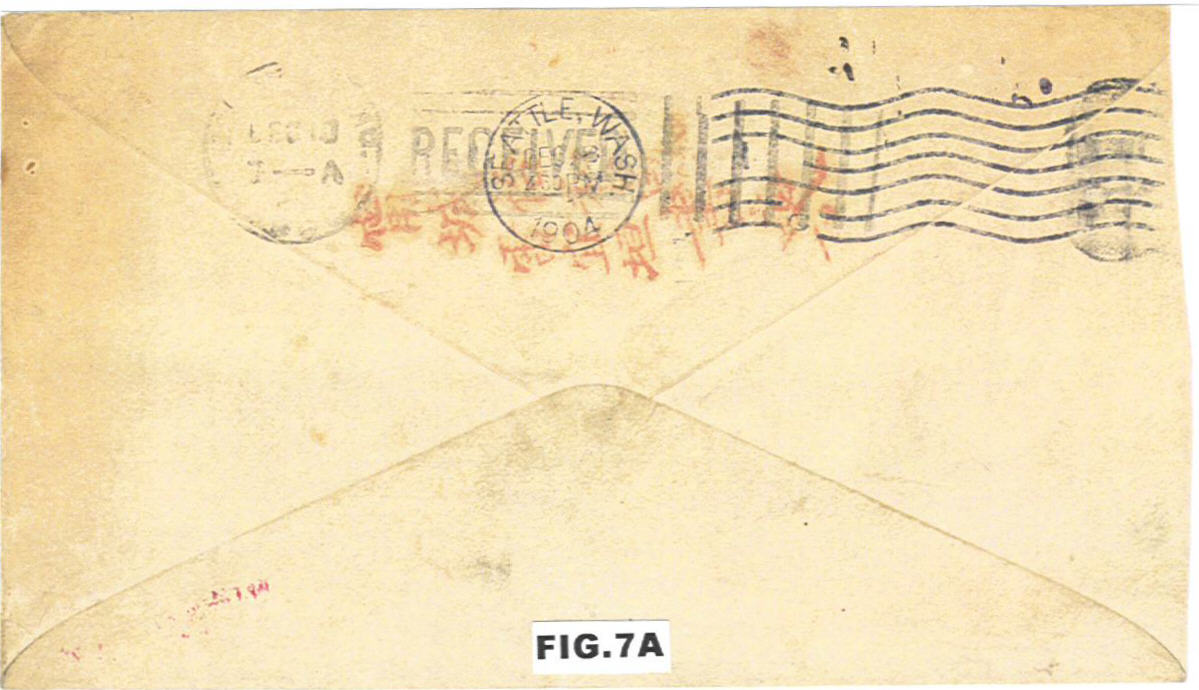

A later example is a 1904 cover to Boise City, Idaho (fig. 7). The back had the marking of Ling Shing (City) ‘Fook Heung Lau, Lui Yee Hung’ stationery/letter/envelope (fig. 7A). Another of the Min Hsin Chu's marking Wong Wah ‘Tin Lui Wai Tong’ stationery/letter/envelope is on the front but without the marking of the HK corresponding office. This is again a cover that had been passed through three Min Hsin Chus.

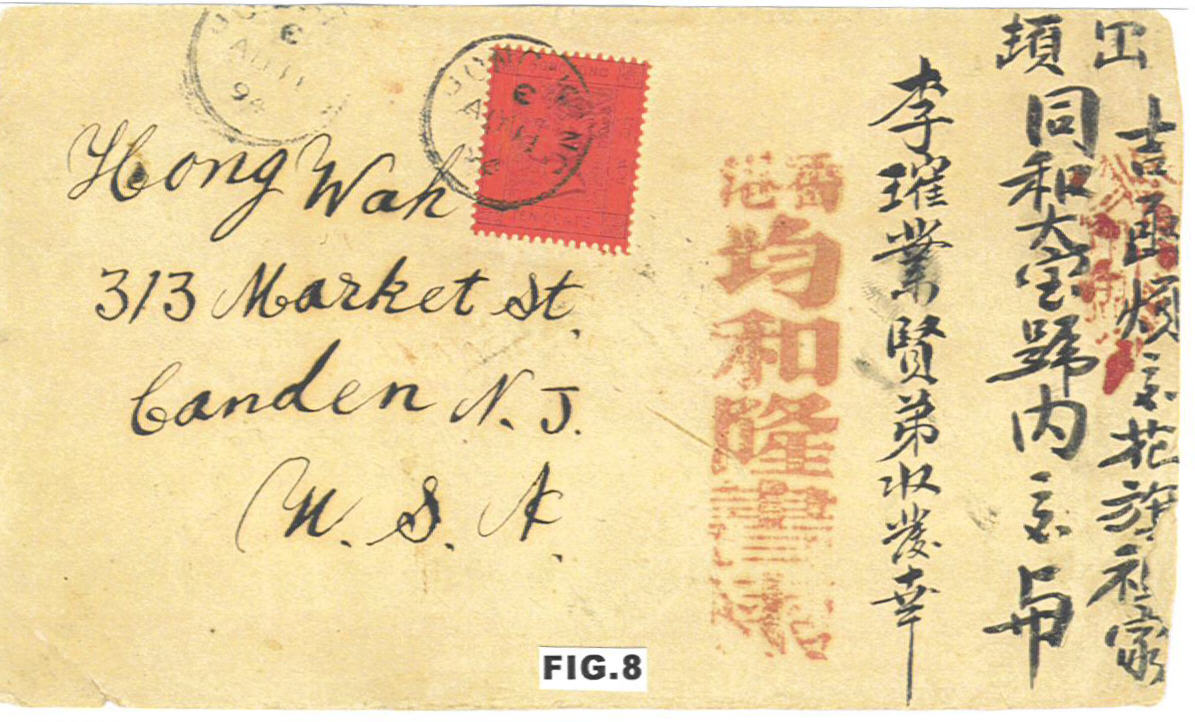

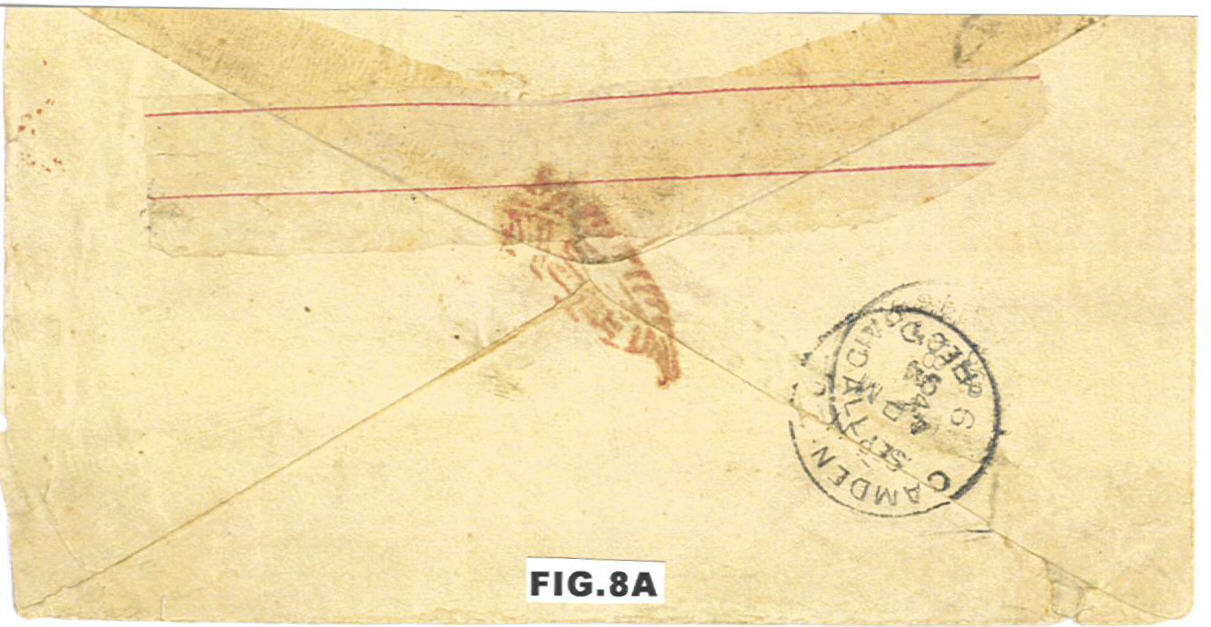

Feather Post or Is it? Previous articles have reported that a Feather Post existed in the liberated area period, 1930-40. In my humble opinion, the feather is merely a sign of good luck when stamped on the covers of this period. Why a feather and not something else? The origin of the feather comes from this saying ''as light as a feather, as heavy as Tai Mountain". Which means that it is not the weight of a letter or the weight of a gift that really matters, but that the thought or the words in the letter weighs much heavier — so heavy that it is comparable to the mass of the Tai Mountain, one of China's famous mountain ranges. An example is this 1894 cover to Camden, New Jersey (fig. 8). The leaf was stamped both on the front upper right corner and the middle of the back sealing the flap (fig. 8A). Also on the front is a Hong Kong ‘Kwun Woo long’ stationery/letter/envelope marking.

So why were there Min Hsin Chu markings’ on covers that seemingly originated from Hong Kong? This is a logical question given that if someone was to send a letter from Hong Kong to the US in 1894, wouldn't it be just as easy to put a stamp on and mail it at the Post Office? Why would they need to go to a Min Hsin Chu in Hong Kong who then imprint their mark on the cover? It is possible that the sender was illiterate and so had to go to a letter-writer to dictate the letter. For a single fee, the letter-writer did the rest for the sender and sent it off by the Min Hsin Chu. Secondly, there was only one post office for the whole of Hong Kong unti11898. To travel to Central to send a letter was just not practical for the ordinary person and so it would be more convenient to use the Min Hsin Chu. Given the ease and availability of transportation in the modern world to Hong Kong's Central, it must be remembered that in the1890's, such a journey would take a whole day. Therefore, it was not a coincidence that when the first branch office was opened at Sheungwan in 1898, the HKPO called it the ‘Western Branch’. It was also still quite possible for these letters to have originated from a Min Hsin Chu in China proper and passed onto their Hong Kong corresponding office. There were however, no markings applied. This is because, as commented upon by Major Pratt, after the PMG sign the agreement with the shipping companies in January 1897, it would be illegal to send non-post office mail via the shipping companies. If found, they, together with the Min Hsin Chu, would be fined and the letter taken away and put into the Chinese postal system with an additional fine which would be levied along with the original postage. Therefore, I suspect that the Min Hsin Chu would be clever enough not to put their markings on their covers. If caught, the Min Hsin Chu involved would not be linked. Despite the fact that these covers did not have Min Hsin Chu markings, one cannot automatically rule out the possibility that these might have originated from China and been forwarded by the Min Hsin Chu. The Lowly Chinese Marking On Turn-of-the-Century Mail from Hong Kong If you go back and look at the cover in figure 1 again, the markings are apparently from Hong Kong but did this letter originate in Hong Kong or China? I hope I have shown you from these few examples (I have more that are not illustrated) that these lowly Chinese markings on a cover that apparently originated from HK were not just a private marking, or just an advertisement for a stationery seller. These letters might have originated from China. And if lucky enough, one can even find items that had the names of the town or village that they originated from on the markings. Some might even have a marking, like the ones in figures 2 and 3 that show the cover was forwarded by a Min Hsin Chu to the Hong Kong Post Office. Most of the examples were posted after 1895 which corresponds to the California Gold Rush and the Chinese workers being shipped off to work in the ‘Gold Mountain’ and beyond. The only way their family could send a letter was by a Min Hsin Chu to the Hong Kong Post Office. What about the return letters? There was simply no way the Customs Post Office could deliver most of the letters to the small towns and villages in Southern China before 1900. The common practice was for the Chinese companies in the major US or Canadian cities to act as intermediates. Footnote |